History of Umpiring 8

By:

In contrast to increased tolerance regarding on-field behavior, the personal lives of umpires received unprecedented scrutiny. In November 1988 Commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti, acting on behalf of club owners, released ten-year National League umpire Dave Pallone because of the fear that the arbiter's homosexuality might compromise his on-field performance and baseball's image. NL president Bill White suspended Bob Engel in April 1990 after he was charged with two misdemeanor counts of shoplifting baseball cards; baseball's insistence upon the unquestioned integrity of umpires prompted the twenty-five-year veteran to retire immediately upon his conviction in July. And in 1991 two unidentified umpires, one in each league, were placed on a year's "probation" because of alleged association with bookmakers even though there was no indication that they had ever bet on baseball games.

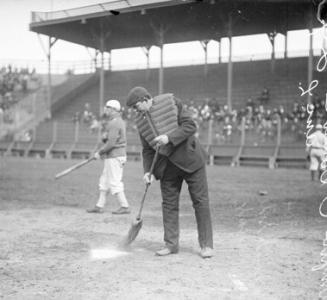

The physical appearance of umpires was also tailored for the public eye. Increased emphasis was placed on size, as taller and more muscular men were in vogue--perhaps to personify the umpire's authority in an antiauthoritarian age. The American League's adoption of gray slacks in 1968 and maroon blazers in 1971 was part of an effort to project a distinctive "sporty" image, as was the case later when umpires in both leagues began wearing numerals on their sleeves and baseball caps with letters designating league affiliation. Similarly, contact lenses were favored over glasses. By the early 1990s the "casual look" was completed when umpires wore short-sleeved shirts without jackets during hot weather and satin warm-up jackets on cool nights. Contact lenses were favored over glasses until 1991 when Al Clark (AL) and Frank Pulli (NL) wore spectacles while umpiring behind the plate as well as on the bases. In 1988 obese umpires were put on weight-reduction programs during the off season; by 1991 those who failed to lose prescribed poundage were subject to suspension pending compliance. For Gargantuan umpire John McSherry, however, the program was to no avail, and he proved an on-field fatality in 1995.

Aside from the superficialities of cap insignia and jacket color, there was little to distinguish the two umpire staffs in appearance. Training in umpire schools and minor league supervision by the Umpire Development Program had the effect of imposing uniformity of style and technique on umpires and thus on the leagues. Moreover, by the 1970s American League arbiters had adopted the inside chest protector, while the National League mimicked the preference for "big" men. However, a reversal in league images also occurred: just as the players in the Senior Circuit were widely regarded as superior to those in the Junior, National League umpires were similarly perceived as better in the 1960s and 1970s; meanwhile, the American League, with umpires like Ashford and Luciano and fiery managers like Billy Martin and Earl Weaver, became more volatile than the now staid National League.

Despite television exposure, heightened after 1969 by intra-league championship playoffs, umpires as a group were personally more anonymous than before. Exceptions like Luciano notwithstanding, the individuality of umpires was submerged by the four-member crew, the numerical expansion of staffs, the rotation among cities, the standardization of styles and techniques, the decline in the frequency of rhubarbs, and the attempt to project a more staid professional image. Few umpires stood out as demonstrably superior to their colleagues, partly because systematic training and preparation had increased generally the competence of all arbiters and partly because professional basketball and football now offered competition for outstanding officials. Nonetheless, there were some premier umpires in the postwar era, chief among them Nestor Chylak and John Stevens of the American and Al Barlick and Doug Harvey of the National League.

During the course of a century of major league baseball, the umpire became transformed from a despised, untrained, semiprofessional "necessary evil" to a respected, skilled professional who epitomizes the integrity of the game itself. In the process some arbiters became immortalized in record books for notable achievements and distinctions. J.L. Boake umpired the first professional league game (1871), Billy McLean the first National League game (1876), and Tommy Connolly the first American League game (1901). Hank O'Day and Connolly umpired the first modern World Series (1903), while Bill Dinneen, Bill Klem, Bill McGowan, and Cy Rigler worked the first All-Star Game (1933). Bill Klem holds the record for most seasons in the majors (thirty-seven), most World Series (eighteen) and most World Series games (one hundred-eight). Al Barlick and Bill Summers worked the most All-Star Games (seven). Doug Harvey has umpired the most League Championship Series (nine) and LCS games (thirty-eight). George Hildebrand holds the record for most consecutive games umpired (3,510). (Babe Pinelli has claimed that he did not miss a regulation game in his twenty-two-year career.)

Emmett Ashford was the first black professional umpire in both the minor (1951) and major leagues (1966), while Armando Rodriguez (1974) was the first Hispanic umpire in the majors. Bernice Gera was the first female professional umpire (1972), although she worked only one game in the Class A New York-Penn League; Pam Postema's bid to become the first woman to umpire in the major leagues ended in 1989 with her release from the Triple-A Alliance after spending thirteen years in the minors. Evans was the youngest (twenty-two) and Klem the oldest (sixty-eight) to umpire a major league game. Eight umpires are enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame: Jocko Conlan (1974), Tommy Connolly (1953), Bill Klem (1953), Billy Evans (1973), Cal Hubbard (1976), Al Barlick (1989), Bill McGowan (1992) and Doug Harvey (2009).

Rich Garcia